I’ve always been fascinated by the question of when the Roman Empire fell. The Old School tradition dates the demise of that massive empire to 476 CE (or AD if you prefer), when Romulus Augustulus was deposed by Odoacer as the last Roman emperor in the West, and sent his imperial regalia to Zeno, the remaining Roman emperor in Constantinople.

I’ve always been fascinated by the question of when the Roman Empire fell. The Old School tradition dates the demise of that massive empire to 476 CE (or AD if you prefer), when Romulus Augustulus was deposed by Odoacer as the last Roman emperor in the West, and sent his imperial regalia to Zeno, the remaining Roman emperor in Constantinople.

But of course, that begs the question: if the Roman Empire fell, how was there still an emperor to send the regalia to? The answer is, of course, that the Roman Empire was ruled jointly from Italy and Constantinople in 475, so the termination of the western half did not mean the empire fell, but rather just continued a process of shedding territory that had begun 70-some years earlier. The Roman Empire as ruled by a Roman emperor in Constantinople (or nearby) endured another millennium falling in 1453 (traditionally) or even as late as 1461 depending on how you measure that. But by then it was a wholly transformed polity, Greek in language, Orthodox in religion, etc., and even the historians who push back against 476 and say the empire endured longer rarely consider the end of something truly Roman to have occurred in the 15th century.

The galaxy-brain take on this question is to say the Roman Empire fell way before 476. Some point to the so-called “third-century crisis” of Rome, which lasted for 50 years straddling 250 CE. During this time, the empire almost completely lost control of its borders, rarely had an emperor live more than a few years, and almost none of them died a peaceful death. For a good chunk of this half-century of crisis, the Empire actually split into three parts, with only the center under control of a legitimate emperor. This period of crisis has always fascinated me, as does the way it came to a close: the emperor Diocletian took the throne and chose to divide legitimate rule into four territorial segments, each ruled by a co-emperor.

In Greek the term for a rule by four people is a τετραρχία (“Tetrarchia”) and this is where the latest look at this time of great upheaval gets its name. Tetrarchia is a solo/cooperative offering by Miguel Marques (published by Draco Ideas) for 1-4 players, lasting 20-40 minutes. And I liked it.

Gameplay Overview:

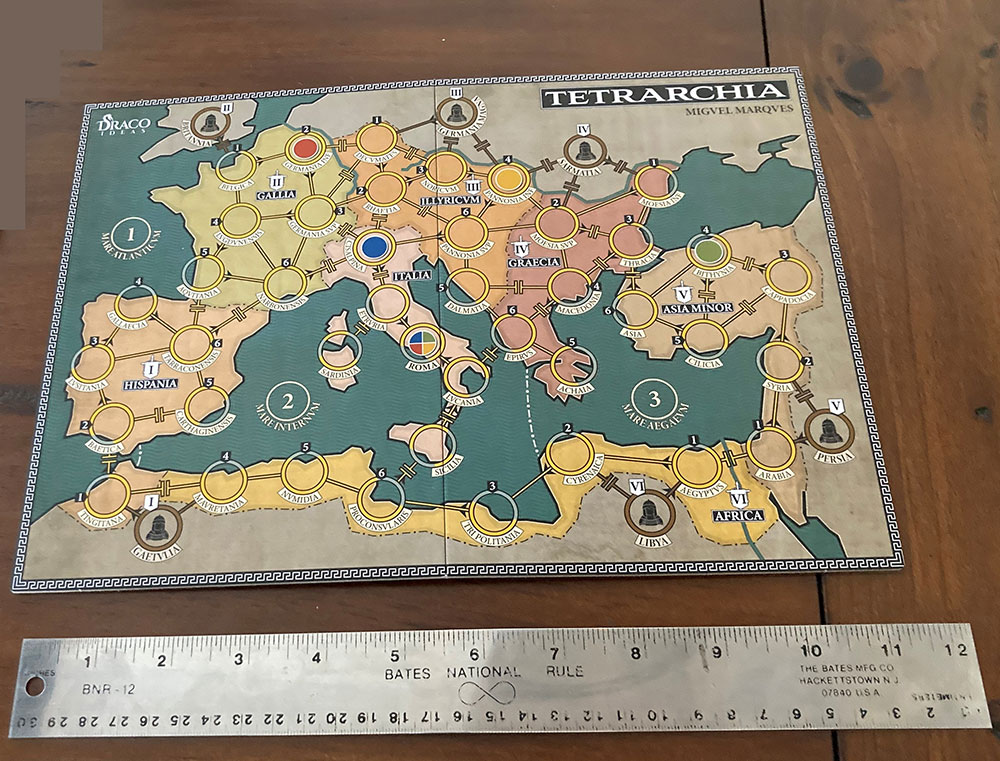

The gameplay is quite simple. You and up to three co-emperors (so 1 to 4 players) choose a level of difficulty (there’s an easy/medium/hard setting but you can also mix and match options to get levels of intermediate difficulty between the three standard settings), put a few pieces onto the very small map board, and then you start play. You can play solo and control all four emperors, split the emperors into two pairs in a 2p, play one emperor each in a 4p, or each controlling one emperor in a 3p while sharing the 4th jointly.

The game rhythm is such that one of the four emperors takes a turn, then the barbarians act up, then the next emperor goes, followed by more barbarian shenanigans, etc… Turn order goes east to west: Diocletian (a senior emperor who starts in Asia Minor) leads off, followed by Galerius (a junior Emperor starting in Illyricum) with barbarians both before and after Galerius. Then the Western emperors take the stage: Constantius (a junior emperor starting in Germania Inferior) followed by Maximian (a senior emperor who starts in Cisalpina), with barbarians before and after Maximian. Repeat until you or the barbarians win.

Game Experience:

The actual turns are fairly simple too. At the start of each emperor’s turn, if he is off the map, he comes onto the board at his capital (if not in revolt) or in Rome. Then, you have six points to spend on actions that generally require 1 or 2 points: movement, mopping up rebellious provinces, placing garrisons, or attacking the barbarians. In combat, simple adjacency rules determine the emperor’s and the barbarians’ strength, which is then added to a d6 roll for each side. Low roller (modified by strength) is removed from the map, high roller takes the spot in dispute. If it’s a tie, nothing changes from the status quo ante as the Romans would say.

On the barbarian turns, things generally go haywire: provinces experience unrest or outright rebellion (and sometimes it spreads to adjacent provinces), barbarians invade, etc. If you stomp out the fires quickly, it all seems pretty easy until one turn you don’t quite eliminate the problems, and then the chaos starts to spread. Three turns later and you’re up to your eyeballs in revolts and a barbarian army or two seems to be on the verge of reaching Rome itself. If you can somehow pacify all six borders of the empire before a barbarian army enters Rome, you win.

If not and the barbarian armies reach Rome, well, it’s 476 all over again.

With a playtime of around half an hour, you probably will have time after a loss to see if you can do better than the real Romans if given a second chance they never got.

While the rules are not complex, it still took me a little while to fully catch on. On my first playthrough, I had not realized that the barbarians take a turn between each emperor’s turn. So, it’s not four emperors, then the barbarians; instead, it’s one emperor, all barbarians, a second emperor, all barbarians, etc. Having the bad guys go four times before your team’s four armies get to move once each makes the game a lot harder, but that was what it took to provide the tense feeling of an empire losing cohesion in every direction at once. Once I figured that out, the game made a ton of sense, and medium and hard settings lived up to their billing.

Final Thoughts

There is a lot of game in this little box (the box is 7 x 9, and the board when unfolded is about the size of a sheet of paper).

Anytime you play against a simple form of artificial intelligence, whether coop or solo, you have to be willing to bring your own excitement to the event – if you stop and think about it too long, it’s easy to realize you aren’t really fighting anything but words in a rulebook. But if you can get past that in Tetrarchia, suddenly you’ve got barbarians at the gates, threatening to overrun your civilization. You and your three co-emperors have to use every last iota of energy to save the Empire. For a game that consists of a board the size of a sheet of paper, about 40 wooden pieces, and two dice, you get a lot of enjoyment per square inch! Sic Transit Gloria Mundi!

Tetrarchia is not an groundbreaking game by any means, but it brings a lot of fun in a very small package, and it mostly succeeds in making you feel those little black discs are actual provinces in revolt, with the fate of the civilized world hinging on whether you can remove them from the map in time. At €30, it makes a worthy addition to any Romanophile’s collection, and could fill a gap for anyone in need of a fun historical solo/coop game that can be played in 30-45 minutes.

Final Score: 3.5 Stars – While not revolutionary with its gameplay, it does bring a lot of fun in a small package.

Hits:

Hits:

• Variable difficulty lets you adjust the game.

• As the challenges mount, you truly feel the tension of an empire stretched just a bit too thin.

• Very simple rules let you can focus on the fun

• Small enough to play almost anywhere.

Misses:

• It’s hard to maintain the fiction of a barbarian invasion when playing against a few lines of barbarian programming in the rulebook.

• It took a while to internalize the rules correctly.