I have no fancy backstory to introduce you to Sandbag. Yes, I once took my family ballooning in Napa, but it’s irrelevant to this review of a game with a balloon name and balloon art, but essentially zero link between the ostensible theme and the game itself. Nevertheless, theme or no theme, I just want to say that I love this game, but I also never want to teach it to new players again.

I have no fancy backstory to introduce you to Sandbag. Yes, I once took my family ballooning in Napa, but it’s irrelevant to this review of a game with a balloon name and balloon art, but essentially zero link between the ostensible theme and the game itself. Nevertheless, theme or no theme, I just want to say that I love this game, but I also never want to teach it to new players again.

Sandbag is a trick-taking card game by veteran designer Ted Alspach, best known for games like Suburbia, Castles of Mad King Ludwig, Maglev Metro, and Ultimate Werewolf and is published by Alspach’s company, Bezier Games. To my knowledge, this is his first true card game, and it’s a real winner. Between 3 and 6 players compete to … do something balloonesque that correlates with scoring the fewest points. Theme-wise, it’s a real clunker but the game play, ooh it’s a hearty stew of brain-breaking twists on the usual trick-taking tropes.

If you like thinky card games and you can tolerate a steep first-game learning curve, this is a real gem of a game.

Gameplay Overview:

The goal of Sandbag is to finish three full-rounds of 12 tricks (so 36 in total) with the fewest points. Players play cards from their hand, but they can sometimes use a card from another player’s “basket” and once per round they will play their “sandbag,” a face-down card with no value and no suit. In general, you’re trying to avoid winning tricks, since a typical trick adds five points to your score, but there are five rocket cards scattered across the game that reduce your score (either by 5 or 7, depending on the player count). However, whether you score five points (bad) or negative points (good), whoever wins a trick must lead the next one and, in a game, where you want to lose most tricks, but with lots of ways to avoid following suit, playing the lead card can be brutal.

At the end of each round of 12 tricks, players add up all the points they won from tricks, being sure to net out the negative points from Rockets, and then add in any of the balloon cards in their “baskets” that were not used by other players during the round.

During the setup for the second and third round, for every 10 full points the players scored (remember points are bad), they get to move an additional card from their hand to their sandbag pile, which gives them a better chance to dodge winning a trick. This is a powerful catch-up mechanism, causing the second round and (especially) the third round of each game to play very differently than the first.

At the end of 3 rounds (36 tricks in all), whoever has the lowest total score wins.

Game Experience:

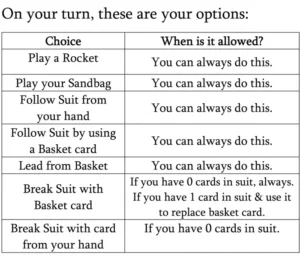

Most of the rules are pretty standard, except when suddenly they are not. So, for example, if no one plays a trump card, the highest card in whatever suit was led will win. You generally must follow suit if you can, but if you are void of the led suit, you may play an off-suit card. If the off-suit card is not in the trump suit, it cannot win the trick, but if that card is in the trump suit, then the highest trump card will win the trick.

All simple enough. But then it gets squirrelly. So, regardless of whether you have cards in the led suit or not, you can always play your sandbag. The sandbag can never win a trick, has no suit, and has no value. It will add a point to the value of a trick (just like every card, other than rockets). So once per round, you can essentially guarantee you’ll lose a trick, which can be handy if the cards in your hand all feel like trick winners.

Also, regardless of whether you can follow suit or not, you can always play a rocket card. Rockets are the source of negative points, and they can only win a hand under very rare circumstances. But sometimes it’s better to toss negative points into the trick (and know you will lose the trick) than to be forced to play a card and win the trick (and gain 5 points).

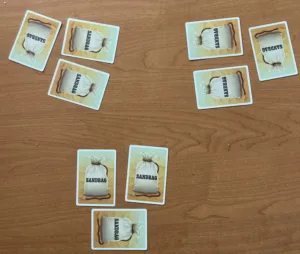

So far, not too hard, but then we have the notorious basket. Every player places two cards in front of themselves at the start of each round. They cannot use these cards, and if the round ends with these face-up cards still in front of them, they will gain points equal to the value of the balloon on the card. Other cards is simply worth 1 point per card, so while losing a trick is typically five points, if you’ve placed a 9 and a 10 in your basket and no one uses those cards during play, you’ll add 19 points to your total. Ooof.

Describing to people when the basket can or cannot be used is where Sandbag’s teach tends to derail. First, you can use any basket card other than your own. If the basket card is in the suit that was led, you can always follow with that basket card. You simply play that basket card to the trick, take any card from your hand, place it face down where the basket card was. The player you took the card from is happy—because they won’t have to eat the points from that card at the end of the round, and you are (presumably) happy because you got rid of one card from your hand while getting to use a better one, assuming you played correctly.

You can also play a basket card off-suit (as trump or not), but only under certain conditions. If you have two in-suit cards in your hand, then you cannot play a basket card off suit. If you have no cards in suit in your hand, then you can play a basket card off suit. But if you have exactly one card in suit in your hand, you can also play an off-suit basket card, but only if the card you place face down to swap for the basket card is that single card of the led suit. In other words, if you end the trick with no cards in the led suit, then it was ok to play that basket card off-suit.

I cannot tell you how many times I have explained that to smart card-game players and had them ask me to repeat it. The rules for playing an off-suit card from the basket if you have exactly one card in-suit in your hand could turn a game-explainer into a basket case.

The rulebook is not well written to cover all these exceptions and the player-aid cards that come with the game only cover some of the corner cases. To try to make things simpler, I created a cheat sheet explaining when you can do every possible play.

I think it makes total sense. Not all the folks I’ve taught this game tend to agree. And then as the explanation drags on and people keep asking me questions (ones that I specifically answered on the cheat sheet), my temper starts to flare, my voice gets louder as I repeat the rule that I explained during the prior trick yet again, etc. It makes teaching this game very annoying.

And then there are the rules about which suit is trump. As mentioned above, when the basket cards are first revealed, whichever suit is most present among those revealed cards is trump.

Because players can play cards from other player’s baskets, and replace them with face down cards taken from their hands, that means at the end of any trick, the trump suit could change, as the suit that was second-most common might now be more common among the remaining basket cards, or might now win the tiebreaker, etc. The actual trump card is determined when the trick ends, though of course as an experienced player, you will be re-assessing trump as the trick proceeds. This is pretty complicated for first time players. “Wait… I thought you said purple was trump? … Well, it was, but now it’s not.” Pity the poor rules explainer if someone isn’t quick enough to handle all of this.

But there is relief. Anyone with a decent sense of how to play card games will internalize the rules after the first or, at the very latest, second round. The third round will go so much more smoothly and then if folks are willing to play again, all subsequent games are such a joy. It’s just a high barrier to entry; getting people there can feel like receiving discount dental work from a barber school dropout.

Final Thoughts:

If you get your group through the first game and they are willing to play a second, you probably have a game-club hit on your hand. The game is peppy and thinky at the same time, and it plays well with 3 but even better as the player count rises to the maximum of 6. I would play this game any time, as long as I didn’t have to teach it. And despite my hyperbole at top, I will continue to take on the frustration of teaching this, because I want to create a regular set of players who want to explore with me the depths of strategy this game offers. It will appeal to hobbyist gamers as well as people who generally just play traditional trick-takers like Spades, Euchre, or Briscola, but only if you can get people over the learning curve. I wish you good fortune and I assure you the view from the basket is worth the effort of filling the balloon with hot air.

Final Score: 4.5 Stars – Already one of my favorites of the genre. But woe until thee who must teach it.

Hits:

Hits:

• A game among players who know the rules is a fast-paced series of fun, hard choices.

• The catch-up mechanisms really change up how each round plays.

• Easy to bring wherever you go and doesn’t take up much space on the table.

Misses:

• OMG, the rules are so hard to explain.

• The players’ aids do not answer the questions new players tend to have.